How it Worked

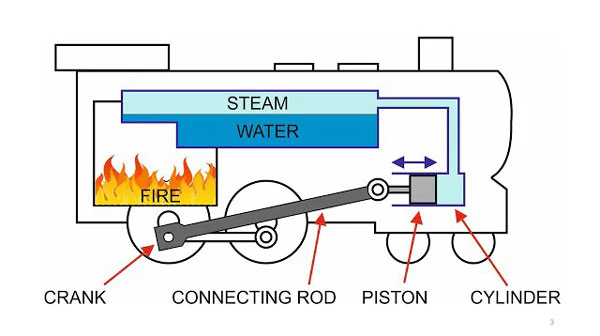

The steam locomotive was a complex and innovative machine that

basically was an efficient method of turning coal into motion to

transport large loads that would be impossible to transport by any

other means. It did this by burning coal to boil water, using that

steam to create motion then transferring the back-and-forward motion

from the pistons to rotational movement of the wheels. These

machines ran on tracks, and in this section we will also outline the

challenges related to these tracks.

The boiler was the part of the steam engine that created the steam

to power the rest of the system, and is vital to the function of the

steam locomotive. The “fireman” would shovel coal into the firebox,

which had a grate underneath to let air through. The heat generated

by the burning coal was then used to boil the water. Which could be

used to power the rest of the system.

The steam power from the boiler was transformed into motion in the

pistons. The steam was trapped to create high pressure, which in

turn pushed up the piston. When the piston got to the end of that

stroke, that steam was released and the valve would switch to

applying the steam to the other side of the piston, pushing it back

the other way. The steam engines in locomotives didn’t use condensing

steam, as that would limit the speed of the engine, and a full

condenser would add weight as well. Another key part of the engine

was the flywheel, which maintained the motion of the pistons. The

flywheel was directly connected to the pistons, and would pick up

speed as the pistons pushed, and when there were gaps, would

continue to provide smooth motion for the locomotive. This was

especially important in early designs that only had a single piston.

However, later engines simply relied on the main wheels themselves

to smooth motion, without the need for an external flywheel.

Now we get to how this back-and-forth motion made by the pistons

gets transformed into the rotational movement of the wheels which

drives the train forward. Attached to the piston, inside the

cylinder, was a hinged rod. The other end of this rod was attached

to a pin which was offset from the centre of rotation of the wheel,

so that as the piston was driven forward by the steam, it would push

around on the top of the wheel, and would reach the front by the end

of its push. Then, the piston would be driven back in the other

direction, and would now pull around on the other side of the wheel,

continuing its rotation. This pattern would repeat as the piston

went back and forth over and over. This system, however, only

powered the wheel nearest to the engine. There was another rod

connected to the same pin that was mentioned, which was connected to

another pin in the same place on all of the other wheels, allowing

the engine to apply power evenly to all of the wheels.

Now we get to how this back-and-forth motion made by the pistons

gets transformed into the rotational movement of the wheels which

drives the train forward. Attached to the piston, inside the

cylinder, was a hinged rod. The other end of this rod was attached

to a pin which was offset from the centre of rotation of the wheel,

so that as the piston was driven forward by the steam, it would push

around on the top of the wheel, and would reach the front by the end

of its push. Then, the piston would be driven back in the other

direction, and would now pull around on the other side of the wheel,

continuing its rotation. This pattern would repeat as the piston

went back and forth over and over. This system, however, only

powered the wheel nearest to the engine. There was another rod

connected to the same pin that was mentioned, which was connected to

another pin in the same place on all of the other wheels, allowing

the engine to apply power evenly to all of the wheels.

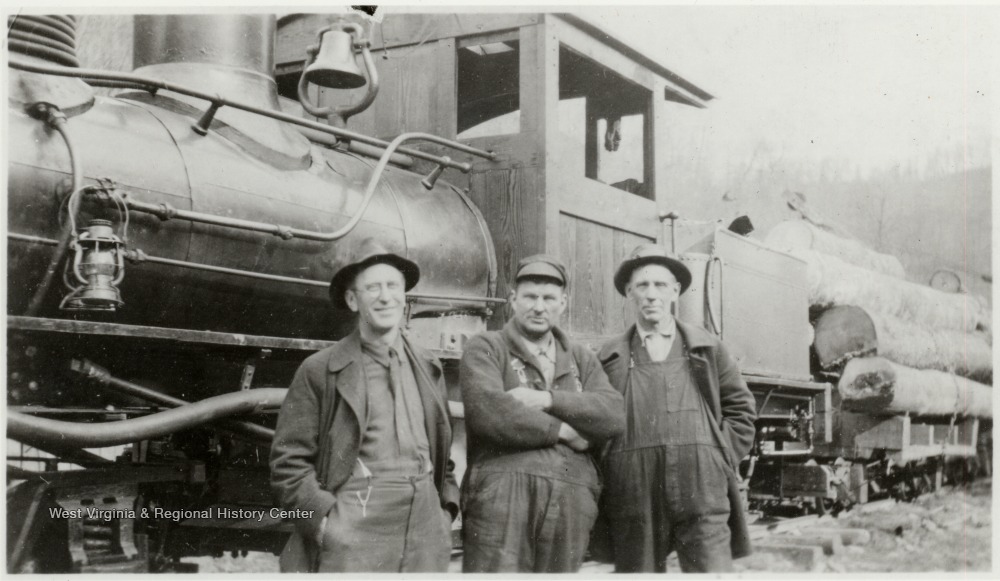

Another vital part of the function of the steam locomotive in the

Industrial Revolution was manpower. There were various roles to be

played in the operation and control of a full steam locomotive,

including the driver/engineer, the fireman/stoker, and the

brakeman/guard. The engineer was responsible for the control of the

engine: operating the speed and direction with the steam regulators

and gears, and monitoring the pressure gauges and water levels, and

watching the track ahead for hazards. The fireman was responsible

for shovelling coal into the firebox to fuel the boiler, managing

the fire to maintain a regular and even heat, and adjusting

temperatures based on the engineer’s instructions. The guard was

responsible for stopping the train with various levers positioned

along the length of the train, and also for notifying the engineer

about track conditions such as obstacles and things and assisting

with the coupling and uncoupling of the carriages.

Originally, steam locomotives were used on the cast-iron rails used

by horse drawn carriages in years before. But it was soon found that

these rails were impractical, as they were too brittle for the heavy

loads that were steam trains, and frequently cracked and broke under

the weight. In 1820, John Birkinshaw invented rolled wrought iron

rails which were significantly stronger than their cast-iron

predecessors and were strong enough to bear the weight of the heavy

steam locomotives. This was a major development that made the

technology much more practical.

Originally, steam locomotives were used on the cast-iron rails used

by horse drawn carriages in years before. But it was soon found that

these rails were impractical, as they were too brittle for the heavy

loads that were steam trains, and frequently cracked and broke under

the weight. In 1820, John Birkinshaw invented rolled wrought iron

rails which were significantly stronger than their cast-iron

predecessors and were strong enough to bear the weight of the heavy

steam locomotives. This was a major development that made the

technology much more practical.

Steam locomotives were complex and innovative machines that utilised

steam pressure from a coal heated boiler to produce motion which was

transmitted through a crank shaft into wheels to run on wrought iron

tracks to carry heavy loads long distances. They had a crew of

people to operate them and were a major development from the

Industrial Revolution.